Roadway deicing operations (RDO) are essential to maintaining safe and drivable road conditions during winter precipitation events. However, these operations can result in the contribution of substantial amounts of chloride to urban waterways. This study evaluates the chloride load applied verses the chloride load delivered via RDO to a stream located in Fort Collins, CO, assesses the impacts of delivered chloride loads on water quality, and applies these findings, in conjunction with pavement performance sensor data, to optimize chloride applications administered during RDO.

Impacts of Roadway Deicing

Overview

In the winter of 2017-2018, the City of Fort Collins Stormwater Utility and Streets Department commissioned a study to evaluate the impacts of RDO on the water quality of Spring Creek. The primary objectives of the study were to:

- Evaluate the amount of chloride applied compared to what was delivered to Spring Creek during the winter of 2017-2018

- Investigate the fate of chlorides that were applied but not ultimately delivered during the winter season

- Summarize the effects of deicing materials on water quality within Spring Creek and how this could impact aquatic life

- Compare changes of baseflow chloride concentrations between the 2011-2012, 2016-2017, and current study

- Analyze roadway recovery attributed to RDO during winter storm events to determine if chloride application can be improved or optimized

The Spring Creek watershed was partitioned into four subwatersheds, each containing a field site where water quality monitoring would take place. In-stream chlorides were quantified by continuously monitoring the four locations along Spring Creek for specific conductivity and collecting grab samples for laboratory analysis during runoff events. Specific conductivity readings were then related to chloride concentration through a linear regression relationship. Combining chloride concentrations with stream discharge measurements yielded the total in-stream chloride loads at each of the four monitored locations for each storm event. In-stream loads of chloride were then compared to the mass of chloride applied by RDO, which was calculated using automated vehicle location (AVL) data supplied by the City of Fort Collins Streets Department. This dataset provided information regarding the time, location, amount, and type of deicer applied by RDO. Additionally, the Streets Department provided the Stormwater Center with pavement performance data so that an analysis could be conducted to determine the effectiveness of current RDO.

Key Findings

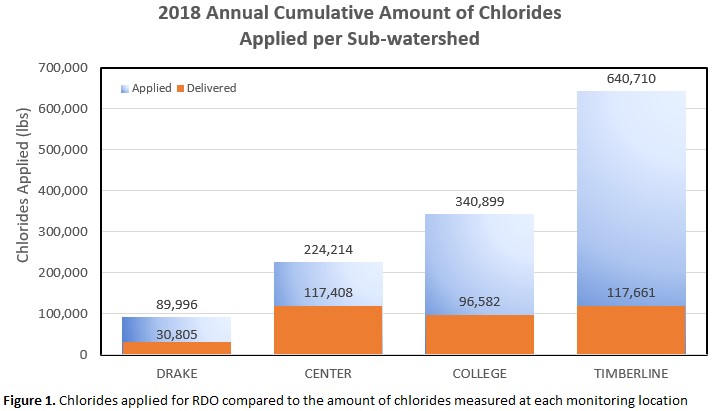

Although there was an abundance of useful information gathered throughout the study, there were two overarching key findings that deserve to be noted. Figure 1 displays the amount of chloride that was applied during snow events from November 2017 until April 2018, and the amount of chloride that was actually delivered to each of the monitoring stations. It is evident from Figure 1 that only a fraction of the deicer applied within each subwatershed was delivered to Spring Creek.

In the most extreme case, the Timberline subwatershed had a discrepancy of 523,049 lbs. between applied and delivered annual chloride loads. Considering the amount of chloride that was not received in the stream, it is clear the natural system has the capacity to capture large amounts of chloride. This apparent storage ability may be closely tied to one of the other key findings, which is related to baseline concentrations. The 2017-2018 study supported a concerning trend that has been witnessed among multiple studies, which is the gradual rise in baseline chloride concentrations after the winter runoff event is over.

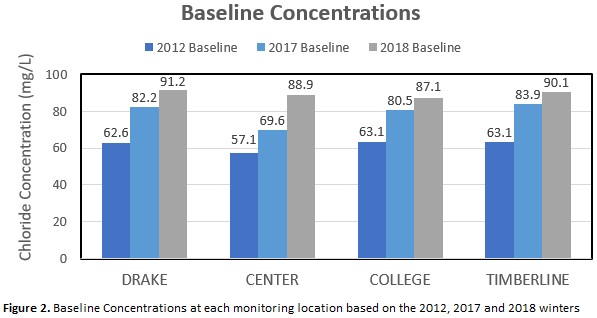

Figure 2 shows that all four subwatersheds had a baseline concentration near 60 mg/L in 2012, which increased over time to a level of about 90 mg/L in 2018. Assuming baseline chloride concentrations continue to rise at the observed rate, it would take the Drake, Center, College, and Timberline subwatersheds 13.3 years, 5.3 years, 6.7 years, and 22.2 years to reach the chronic toxicity level of 230 mg/L, a level set by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment for water to be used as a drinking water source. It has been theorized that this trend is being fueled by local chloride reservoirs gradually leaching chlorides back into waterways. Although rising chloride levels may be a concern, they are not to the extent that water habitat or supply is severely threatened as of yet.